The Rainforest Around us

From the Summer 2024 Issue

Watery weather creates unexpected environment

CEDAR TREES AND FERNS IN THE PRIEST LAKE AREA ARE THE TYPES OF SPECIES FOUND GROWING IN A TEMPERATE RAINFOREST. PHOTO BY DOUG MARSHALL.

Hikers who visit North Idaho from west of the Cascade Mountains might feel more at home here than they anticipated. Many of our favorite hikes pass through an inland temperate rainforest that looks and feels like forests west of the mountains. Having expected to stroll among ponderosa pines, visitors instead recognize the feathery fronds of western redcedar and the tipped-over tops of western hemlock.

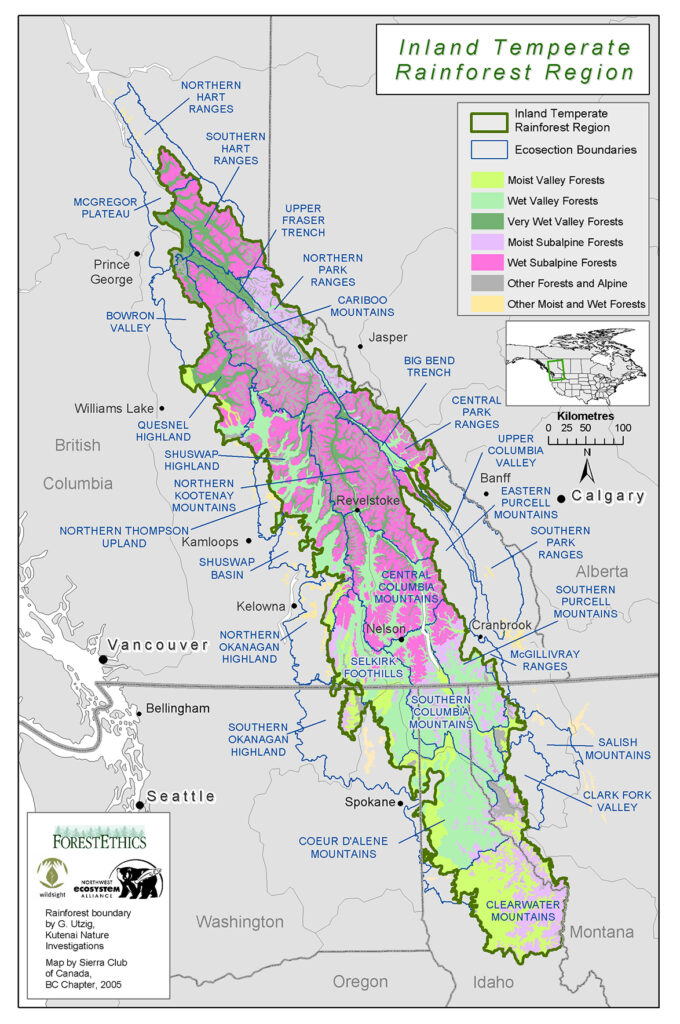

What’s happening here? Many areas around Sandpoint are discontinuous parts of a forest type that is otherwise rare east of the Cascades, although common west of them. This environment is remarkable not only for having plants that are more prevalent along the coast, but for the variety and number of them it supports: “There are no other inland temperate zones on earth that harbour so many species,” avows the Canadian conservation organization Wildsight, which monitors this rainforest as it extends into British Columbia.

A temperate rainforest is different from a tropical one. It is defined in part by “cooler annual temperatures [and] more rainfall“ than the areas surrounding it, said Preston Andrews, a local plant scientist. “The driest part of the year has significant precipitation, so it’s not really a strictly dry summer,” as is typical east of the mountains. “About a quarter of the precipitation comes in the summer,” he added.

We have our local mountains to thank for this peculiarity. Weather systems traveling west to east are forced up to get over the Selkirks, Cabinets, and Purcells, and their clouds must drop rain or snow to gain the height to pass.

THE SHOOTING STAR IS A FLOWER THAT CAN GROW IN BOTH RAINFOREST AND MOIST OPEN WOODLANDS LOCALLY. STAFF PHOTO.

MAP PRODUCED BY G. UTZIG, P.AG. AND SIERRA CLUB OF BRITISH COLUMBIA FOR YELLOWSTONE TO YUKON CONSERVATION INITIATIVE.

Not all nearby hikes are in the rainforest. Local geographic variation means that this type of forest appears in some parts of our region but not others. Rainforest species are found where the altitude, snowmelt, summer rain, and slope orientation provide what these plants need to grow and thrive. In any given area, cooler, north-facing slopes may exhibit the characteristics of the rainforest, while sunnier southern slopes may instead support species more adapted to drier climates, such as ponderosa pine and western larch (tamarack). A hiker crossing a ridgetop may thus experience both on a single trail.

While these conditions create areas amenable to the creation of a rainforest, there is reason to wonder how species that appear to have developed on the west coast got to these inland areas. Their presence is especially remarkable given the expanse of dry, inhospitable land between the coast and here.

There are two theories about this, and both may be true.

It appears that some species migrated north from some of the drainages of the Clearwater River. At one time this area was much closer to the coast, and it was not covered by glaciers as the areas to the north were.

Even more rainforest species appear to have migrated here from the rainforest on the West Coast. “It’s remarkable how plants that are immobile can find ways of dispersing to locations that are favorable for growth,” said Andrews. “Well over a hundred species that are mainly coastal have moved to this inland area.” These plants could have arrived as seeds in the stomachs of migrating birds or on the fur of other migrating animals, including humans—such as the coastal people who for millennia traveled to Celilo Falls on the Columbia River to trade with people from the interior.

The coastal plants we have here include many lichens, mosses, and fungi that are rarely the focus of the casual hiker. But several species will be familiar to travelers from both sides of the mountains, including red alder, licorice fern and sword fern, buckthorn, Rocky Mountain maple, and, in the spring, varieties of shooting stars, lady’s slippers, and mariposa lilies.

Not only does the rainforest have a lot of species, it has a lot of biomass in general. For this reason, it is one of the few parts of the continental U.S. that can support “a full complement of large carnivores,” as one source describes them. It’s why we have relatively large numbers of animals near the top of the food chain, including grizzly and black bears, lynx, wolverines, and cougars.

Hikers may traverse the rainforest in many areas around Sandpoint. The Waterfall Trail from the Schweitzer roundabout descends into the rainforest as it approaches the falls, and Mickinnick Trail passes through it in the dark, cool grove of trees just past the first bench. Rainforest species line the Ross Creek, Spar Creek, and the East Fork Lightning Creek trails as well.

As the Earth warms, this unique environment may be starting to vanish from the interior, and this may not be something humans can change. But we might stave it off for a few generations by limiting encroachment from logging and recreation. “Plants are very resourceful,” said Andrews. “They will find ways to survive. We need to protect the areas that we know exist for as long as we can.”

Indeed we do. That green, shady forest is a great place to escape to on a hot summer day.

SandpointMagazine.com SANDPOINT MAGAZINE | 41 rainforests around us IN THE KANIKSU NATIONAL FOREST NORTH OF PRIEST RIVER, NUMEROUS TRAILS WILL LEAD YOU INTO NORTH IDAHO’S TEMPERATE RAINFOREST. PHOTO BY LELAND HOWARD.

where are these trails