The Secret lives of of Fishes

From the Summer 2015 Issue

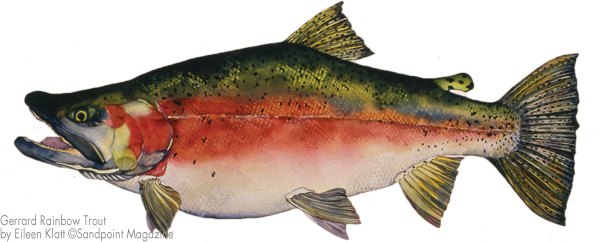

Photos by Pete Comstock, Eileen Klatt, Ward Tollbom

Fish are wildlife, too. In a place so rich with animals, that’s something easy to miss. We know our mammals are amazing – moose, deer, bear, wild canines and cats, weasels and more are animals you can spot here. Our birds are amazing, too: magnificent ospreys and eagles are common, waterfowl crowd in by the thousands, species from tiny hummingbirds to great blue herons are all easy to see.

But fish? Even in a landscape distinguished by great lakes and rivers, most of us know about our fish mainly from those photos of a grinning fisherman showing off a big one.

It’s a case of out of sight, out of mind. Most of us can’t get underwater to see the fish. But our fish are amazing too. And they’re amazing all over the place, not just in Lake Pend Oreille.

The lake produces those oft-photographed trophy-size mackinaw and Kamloops trout, and the plentiful land-locked salmon called kokanee. But those are only the marquee fish, if you will – and guess what? They’re not even native. There’s a whole bunch of other species around here, native and newcomers.

It’s time to meet the amazing fishes of northern Idaho.

Famous Fish of Lake Pend Oreille

In the fall, like the changing leaves, the sleek silver body with the blue-green back grows orange, red, then scarlet. A hump swells behind a now dusky green head, and the skin thickens to appear leathery. The males develop a kype – prominently hooked elongated jaws overfilled with sharp teeth – the metamorphosis to a fighter, preparing for a final battle.

Kokanee, a landlocked variety of sockeye salmon, sexually mature around age 4. The radical alteration of their appearance, prior to spawning, signals the end of their life cycle. Returning to where they originally hatched, females use their tails to cut depressions in the gravel, creating a nest called a redd. With tearing teeth and body blows, the males compete for females and defend their territories. Once eggs and milt are deposited into a pocket of the redd, the female darts upstream and uses her tail to cover the pocket with a protective layer of sand and gravel while building a second pocket. This process repeats two or three times before the female runs out of eggs. She’ll guard the nest until, her energy depleted, she drifts downstream and dies. The males die soon after.

The following spring, when water temperatures warm into the 40s F, the pale orange eggs begin to quiver until a tiny tail or head pops through the shell. Shaking ensues until a new kokanee, known as alevin or sac fry, emerges. Near the throat, an attached yolk sac provides oxygen and food for the alevin, which hides deep in the nest’s gravel, allowing its body to complete development. Weeks later, the kokanee fry form schools and migrate, mostly at night, back into the lake.

Kokanee didn’t exist in Lake Pend Oreille (LPO) prior to washing in from Montana, during a period of flooding circa 1933. The populations exploded to form the cornerstone of a world-class trout fishery.

Kamloops refers to a strain of redband rainbow trout found in the interior of British Columbia, Canada. Within Kootenay Lake exists a genetically superior strain known as the Gerrard Kamloops – a fish that matures slower and lives longer, but grows faster, stronger and larger than any other Kamloops.

In his book, “About Trout: The Best of Robert J. Behnke from Trout Magazine,” Behnke describes the difference between a Gerrard and standard Kamloops as equivalent to comparing a rare “estate-bottled” wine with the “vin-ordinaire.”

Between 1940 and 1943, Gerrard eggs were procured from Kootenay Lake, hatched and released in LPO. Feasting on a diet of kokanee, the Gerrards thrived. In 1947, six years after the first release of fry into LPO, Wes Hamlet pulled a 37-pounder from the waters, a world record that stood for more than 50 years.

Native bull trout that fed primarily on whitefish, native cutthroat and minnows also benefited from the abundance of kokanee. In October 1949, Nelson Higgins landed a whopping 32-pound bull trout from LPO, a world record that still stands.

A school of kokanee moves through a patch of zooplankton on the lake’s surface, feeding by screening water through their gill rakers. From below, a shadow plunges in and grabs a kokanee. Terrified fish scatter. The Gerrard heads for deeper water, gripping its struggling prey. Out of the darkness, a large, steel-colored fish with silvery spots torpedoes through the water, homing in on the fleeing Gerrard. Huge jaws gape and with a mighty snap, the mackinaw, or lake trout, engulfs the back half of the Gerrard. Three fish flail in the water, but only one survives.

With good intentions, the federal government introduced mackinaw to LPO and Priest Lake in 1925. Like a sleeper cell, the fish spent the next 50 years acclimating to the environment, but lacked the trigger to make conquest of the waters doable. The juvenile macks required a suitable and consistent food source.

During the 1960s, a clamor rose among anglers for better food to grow bigger kokanee, which led to the introduction of mysis shrimp. Then, the unthinkable happened. The kokanee fishery crashed.

According to Idaho Fish and Game (IFG) Panhandle Region Fishery Manager Jim Fredericks: “Unfortunately, shrimp didn’t turn out to be good feed for kokanee. It wasn’t that the kokanee wouldn’t eat shrimp, it was more about availability. In the daytime, when the kokanee are feeding in the upper water levels, shrimp are way down deep at 400 to 600 feet. At night, when the shrimp come to the surface, the kokanee aren’t feeding. So, they eat them when they see them, but they just don’t see them.”

The influx of shrimp where juvenile mackinaw lurked increased survival rates among the young macks. Meanwhile, shrimp feed on zooplankton. Widespread competition for food combined with more predators in the “pond” devastated the kokanee population. By the 2000s, the implementation of drastic measures to ensure their recovery included closing the fishery to anglers.

Unlike bull trout, which needs “the best of the best” in terms of spawning and rearing tributaries, or the Gerrard, which only thrives on kokanee, mackinaw make do with a variety of prey, less than perfect habitat, and have the added advantage of living decades longer than any other trout in the lake.

“If there aren’t fish to eat, lake trout can actually do fine eating invertebrates, mysis shrimp, insects, or whatever they can find. They are not going to starve out and die,” said Fredericks.

As proof, the Idaho record for mackinaw came out of Priest Lake in November 1971. Lyle McClure landed a monster that weighed 57.5 pounds.

The previous kings of the panhandle waterways, the native bull trout, remain viable in LPO, Priest Lake and surrounding streams but are listed currently as a threatened species.

According to Fredericks: “Historically, bull trout were going hundreds of miles – way up past Missoula in the Clark Fork to spawn. So there was a tremendous amount of spawning, rearing habitat and Pend Oreille was their ocean.”

Requiring water temperatures from 40 to 50 F that are oxygenated and sustain a high level of purity, a stream habitat with both riffles and deep pools, and connections between lakes and tributaries, the bull trout’s domain shrank with the building of dams and higher levels of sediment in streams.

While not growing as large as other trout, native cutthroat trout, Idaho’s state fish, flourishes in the lakes and streams of northern Idaho. There are 14 strains of cutthroat of which three – the Yellowstone, Bonneville and Westslope are natives. In the panhandle the latter strain prevails.

Higher water clarity typically indicates fewer nutrients for fish. Cutthroat, distinguished by the red slash under their lower jaw, adapted to Idaho’s crystal clear streams by aggressively striking at anything that might be food, making them a favorite among anglers.

Between reducing mackinaw and rainbow populations and bolstering natural spawns with hatchery produced fry, the kokanee population now shows strong signs of recovering. This is good news for anglers and all the fish in the system.

Leave a comment