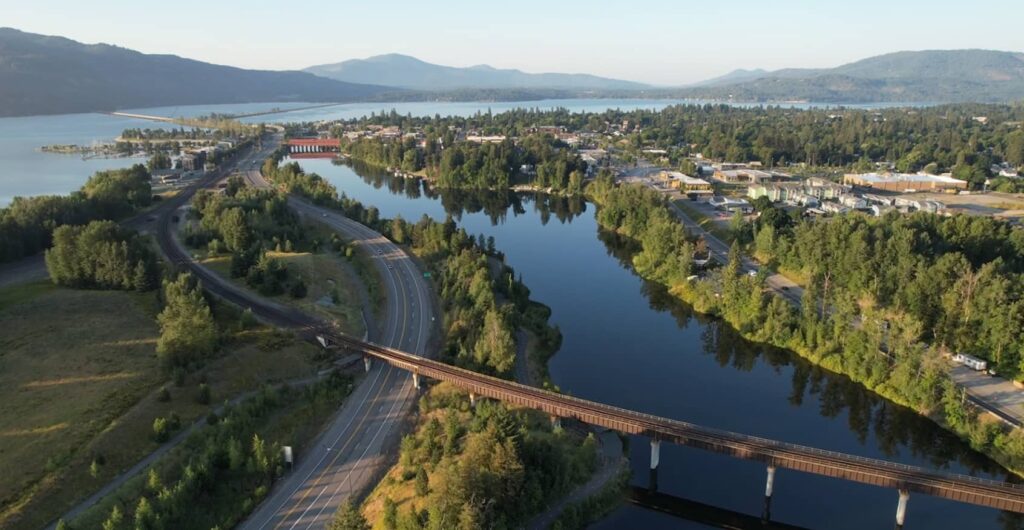

Wonderful Waters

From the Summer 2024 Issue

Sand Creek's hidden treasures

PADDLE BOARDERS ENJOY THE PEACE AND QUIET ALONG SAND CREEK. PHOTO BY JASPER GIBSON.

Hidden in the midst of our ever-more-densely populated urban area, Sand Creek threads furtively through an emerald ribbon of backyards on its last few miles to Lake Pend Oreille. Ducks paddle undisturbed in the quiet water. Moose wade in the shallows, otters play along the shore, and eagles and osprey patrol overhead.

With private property on both sides and few public access points, this languid stream doesn’t see the intense summer action that occurs downstream at the beach. But the creek itself is a public waterway, and as such it is a quiet haven for small, human-powered boats. Admittedly, it’s a short one—upstream of the Schweitzer Cutoff Bridge, it’s not navigable, even in a canoe in high-water summer. It is decidedly not the next great water playground of Sandpoint’s summer denizens.

Instead, it is a place of refuge. “Everything in town is being developed, built on, and changed—Sand Creek is a place to go to get away from the development surrounding us and enjoy a slice of nature,” said one appreciative local.

The question will be how to keep it that way.

Kaniksu Land Trust got involved with planning a sustainable future for this green ribbon at the request of multiple stakeholders: surrounding landowners, recreational users, local governments. It initiated the Sand Creek Connections project to envision how best to maintain this Eden as change presses in from all sides.

As is common with KLT projects, many partners are involved. The project’s steering committee includes representatives from the city of Sandpoint, the Kinnikinnick Native Plant Society, and the city of Ponderay, as well as three property owners along the creek, and the Kalispel tribe. An advisory committee extends further to people and organizations with expertise in water quality, plants, fish, conservation education, and land use planning.

ONCE PAST THE CEDAR STREET BRIDGE, SAND CREEK OFFERS THE IDEA OF SECLUSION DESPITE ITS LOCATION IN THE MIDDLE OF TOWN. PHOTOS BY JASPER GIBSON.

The National Park Service has been involved too, in what is perhaps a first for our area. Its Rivers, Trails, and Conservation Assistance program has provided planning and technical assistance.

The goal is to create a community vision document with action strategies based on community goals. This will serve as the basis for more public engagement at an open house during the summer of 2024.

Access to the creek is currently quite limited. Visitors can launch their craft at City Beach or at the east end of the Bridge Street Bridge. (By 2025 they will have another option after the city builds a planned small-craft launch at the Visitor Center on Highway 95.) They can paddle north as far as Cedar Park, a little-known and quite small public area just upstream of the Schweitzer Cutoff Bridge. There, in summer’s high water, they might step out of their probably-aground craft and have a picnic ashore.

Or they can launch on the west side of Popsicle Bridge, which is public property, but problematic. “The Popsicle bridge gets a lot of use,” said Regan Plumb, conservation director for KLT. “The access is terrible to get your canoe or kayak in, but people still do it. And there’s no parking. There’s no trash [can], there’s no bathroom.” The resulting accumulation of human detritus is an annoyance to those who are otherwise fortunate to live nearby.

In the future, there might be more access at a site just downstream that KLT owns and plans to give to the Kalispel tribe. The tribe plans to keep it open to the public, while leaving it in its natural state.

ONCE PAST THE CEDAR STREET BRIDGE, SAND CREEK OFFERS THE IDEA OF SECLUSION DESPITE ITS LOCATION IN THE MIDDLE OF TOWN. PHOTOS BY JASPER GIBSON.

A PADDLE ON SAND CREEK OFFERS A QUIET RESPITE. PHOTO BY REGAN PLUMB.

Because much of the land along the shore is privately owned, there is little hope for any extension of the creekside walking and biking trail that runs from the Bridge Street Bridge north under the highway and on to Popsicle Bridge. But there is still hope for a trail along the west side, below the big new houses. Many in Sandpoint recall that when the University of Idaho sold this creekside land to private developers, there was a promise that a public trail would be created next to the water. Conversations and negotiations continue about this path, which will extend south from the Popsicle Bridge.

But is encouraging access to this remarkable sliver a good idea? It appears to be the best alternative. A survey of neighbors and other interested parties, conducted this past winter, indicates that they want the creek to continue as a haven of peace and quiet. But they know that people will continue to come, and they recognize that planning for them is their best hope to preserve it.

Beyond the desire for peace and quiet is the question of how human use will affect the water’s cleanliness and clarity. Upstream it is, after all, a source of drinking water for the city. “Water quality is huge, a really high priority, and something that keeps coming up over and over in all of our outreach,” said Plumb. Numerous comments on the survey mentioned the presence of invasive plants, and the vision will include a strategy to mitigate those and encourage the return of displaced natives.

But if people are to continue using the creek without damaging it, education will be a necessity. That is part of the project, too, although the form it will take is as yet unspecified. The idea is that public access points can be used to help people understand how they can visit in a way that keeps the waterway healthy. In order to minimize signage in the natural environment, a mobile app is one of the options being considered.

Hopeful quiet paddlers, wildlife lovers, and shoreside walkers should keep an eye on KLT’s website (www.kaniksu.org) to find out the date of the open house this summer. A draft of the vision document may be on the website as well. Planning will wrap up by the end of 2024, when grant writing to fund the vision will begin.

Leave a comment