Sages of Sandpoint

From the Winter 2014 Issue

photography by Jesse Hart

Sandpoint is full of remarkable individuals, but these four sages, all men in their 90s, are special not only because they are doing remarkable things but because they’ve been doing them for a remarkably long time.

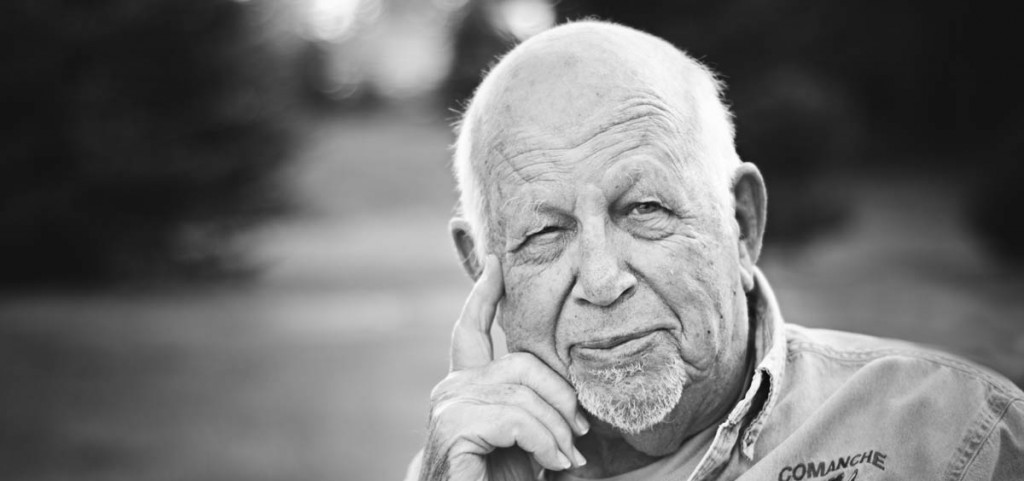

Forrest Bird, 92, aviator, inventor and biomedical engineer

Encouraged by his father, a World War I aviator, Dr. Forrest Bird learned to fly when both he and aviation were quite young. He completed his first solo flight at the age of 14, nearly 80 years ago, and by 16, he was working toward earning major flight authorizations.

In 1937, he witnessed aviation history twice. Around noon on May 6, he flew his father’s 1927 Waco next to the doomed Hindenburg airship as it passed near his Massachusetts home; it exploded in flames just hours later. That fall, on a trip to the Cleveland Air Races, he met Orville Wright.

“I looked up to him because I loved aviation, and he started it,” said Bird.

By the time he entered the Army Air Corps in 1941, Bird already had so many hours of flying time that he was able to advance quickly, piloting nearly every aircraft in service. During and after World War II, he worked on breathing devices for flying at extreme altitudes, and this led to an interest in making breathing apparatus for medical uses. He tested his respirator by traveling in his own airplanes to medical schools and asking doctors for their most ill patients. He married a Sandpoint girl, Mary Moran, and built his business and home on 300 acres in the woods south of Sandpoint, at the end of the road on Glengary Bay.

Although he has more than 200 patents to his credit, Bird is most famous for having developed respirators for patients with lung problems. The first Bird Universal Medical Respirator, later known as the Bird Mark 7, went into production in 1958. The more recent models, now known as Percussionators, ventilate “kinda like a dog pants, very rapidly,” as he puts it. Ironically, Mary contracted pulmonary emphysema. Using her in his research, Dr. Bird perfected his Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilator, extending her life for 10 years before she died in 1986.

He is most proud of his ventilator for infants, nicknamed the “Babybird,” which has saved more lives than anything else he has invented. It gives newborns with respiratory problems a chance to survive until their lungs are ready to support them. Introduced in 1970, it reduced respiratory-related infant mortality from 70 percent to 10 percent.

Despite the fame of his inventions, Bird kept a relatively low profile in Sandpoint until he and current wife, Pam, opened the Bird Aviation Museum and Invention Center in 2007. The entire town of Sandpoint was invited to his 90th birthday party there in 2011, at which, to his surprise, he was awarded another of his numerous awards, the American Association of Pediatricians Neonatal Pioneer Award for his contribution to the care of newborns through the Babybird.

Other accolades include the Presidential Citizen’s Medal, awarded by the second President Bush, and the National Medal of Technology & Innovation from President Obama. In 1995 he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Local appreciation for him is more tangible; readers might recognize his name from the Forrest Bird Charter School.

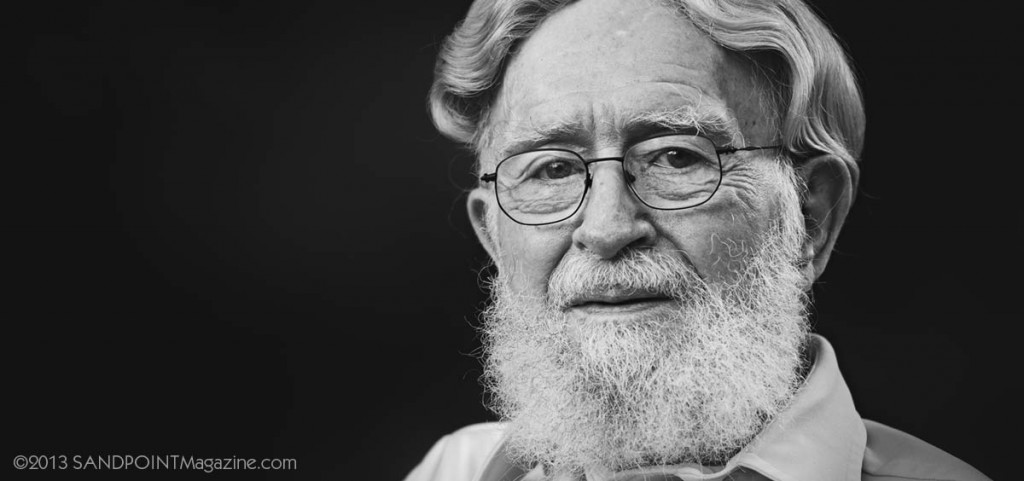

Paul Rechnitzer, 95, historian and author

“If you’re going to move to a new place, it behooves you to get acquainted with where you are, and learn to like it and become a part of the community,” said Paul Rechnitzer. Because Rechnitzer is good at following his own advice, pieces of northern Idaho’s past have come alive for local residents. His books will ensure this history is not forgotten again.

Rechnitzer discovered northern Idaho during his travels in a career as a salesman with Phillips Petroleum. When he retired in 1977, he settled on a 70-acre parcel south of the Pend Oreille River at Seneacquoteen. He soon discovered that for countless centuries, native people and later European explorers had crossed the river near his home, and when he realized the house across the river was the historic residence of a ferryman, he started asking around. What began as an article about the ferry for the local paper turned into “Always on the Other Side,” a book about 14 different ferries that once served travelers along the river.

Soon to follow were “Take the Train to Town” and “Corbin’s Road,” two histories of the rail lines that still dominate “the funnel,” as Sandpoint is known among railfans. The current railroads are far less colorful than the historic ones Rechnitzer discovered: “The financial shenanigans now are nothing compared to what it was in those days,” he said of the railroad men who routinely issued, manipulated, sold and reissued stock in their companies. “We’re all just Sunday school boys compared to those guys.”

Rechnitzer frequently makes presentations about the ferries and the trains. He has an engineer’s cap from each of the historic railroad lines, and he changes caps as he talks about each one. He likes to point out that he doesn’t have a PowerPoint presentation: “I have a hat presentation.”

A model train that passes through a model of Sandpoint fills a building behind Rechnitzer’s current home in Sagle, conveniently located near actual railroad tracks. In honor of Armistice Day in 2009, Rechnitzer created a World War I exhibit featuring model aircraft displayed at the Sandpoint Library. Recently he has turned his modeling skills to a set of soldiers to represent the African-American outfit he commanded in World War II.

“I’m constantly irritated by the fact that these guys never got any recognition,” he said.

His hand-painted soldiers, each man 3 inches tall, attracted the attention of the Army Quartermaster Foundation in Fort Lee, Va., and they awarded Rechnitzer the Order of Saint Martin for his efforts. The soldiers, however, remain on patrol near the trains; he’s yet to find a permanent home for them.

Rechnitzer’s advice for those younger than he reflects a particular trait that has made him successful as both a salesman and a historian: “The best conversationalists are those who listen. I listen as much as I can; hopefully I’ll learn something.”

Charlie Glock, 94, sociologist, tinkerer and deep thinker

Charlie Glock has never been one to shy away from life’s biggest questions.

During an academic career spanning more than three decades at Columbia University and the University of California at Berkeley, he published numerous books and articles in the fields of social research and the sociology of religion, with a particular focus on religious belief and prejudice.

Based on surveys he and a colleague conducted among parishioners of various Christian churches, he coauthored “Christian Beliefs and Anti-Semitism,” published in 1966. His work was discussed at Vatican II, an international council of Catholic leaders, and he traveled the United States meeting with Protestant congregations to discuss the issue. The Anti-Defamation League identified this work as having helped improve interfaith relations.

Anyone who was around Berkeley in the 1960s will recall that it was not a calm and peaceful place, and addressing anti-Semitism could not have been a restful pursuit either. Glock started woodworking to take a break from a sometimes stressful academic life. When he retired to northern Idaho in 1979, his interest in woodworking came with him, and his Sandpoint garage turned into a workshop.

Here he has created a locally famous collection of kinetic sculptures that share a basement room with his furnace and shelves of books from his days in academia. Made of wood and small electric motors, the sculptures drop marbles, spin disks or move arrows in a variety of intriguing patterns. Glock enjoys pointing out that, in contrast to his academic work, the sculptures accomplish nothing at all, although they do require a great deal of thought and experimentation.

“It is extremely difficult to describe how these things work,” he said. (Search “Charlie Glock’s kinetics” on YouTube.com to see a series of six videos on them.)

Other retirement pursuits have included singing baritone in the Pend Oreille Chorale and creating a “4-H” group for members of his generation to exercise together: the Healthy Hale Hearty Hellions. They had matching T-shirts made with their 4-H club name, and the members worked out at Sandpoint West Athletic Club. Glock credits this habit with having had a significant effect on his health and longevity.

Meanwhile, Glock hasn’t abandoned the big questions. He has been running a weekly “scholars” discussion group at the library for 15 years that would keep anybody mentally fit: “We’ve been dealing recently with the subject of creativity,” he said. Having completed his memoirs and a novel, he’s working on a new book, “The Ways the World Works: Free Will and Determinism in Everyday Life.” It addresses the question: How do we decide whether we are in control or are in the control of someone else?

“The book will be hard to finish because the question is hard to answer,” Glock said.

Joseph Henry Wythe, 93, architect

Joseph Henry Wythe was studying architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, after World War II when a field trip to the navy’s Seabee base at Camp Parks changed his life. There he saw the work of Bruce Goff, who had designed a series of imaginative buildings using the limited resources and materials available during wartime. After that, Wythe realized he had no interest in the architecture he was then being taught.

“There was a big turnaround in my designs and everything else,” said Wythe. “It was a completely different world I entered into.”

He left Berkeley to join Goff at the University of Oklahoma, where he finished his degree and joined the architecture faculty.

Wythe and Goff’s approach to building is based on the concept of “organic architecture,” a term coined by architect Frank Lloyd Wright, a close friend of Goff and a figure that Wythe is proud to have met.

“Upon encountering a work of organic architecture, most people are delighted with the experience,” writes Wythe on his website, alternative-architect.com. It represents a style of building that draws one in and is in harmony with its natural surroundings.

“Wright said all schools of architecture ought to be shut down, and he’s correct,” said Wythe. “They’ll teach you technology, but they don’t teach the art.”

Wythe’s students were required to study art before they studied architecture; only then could they be trusted to begin to design. Once they had studied art, he asked them to draw what he calls “archidoodles” – bits of line and curve. These can eventually be incorporated into an overall building design that appeals to the human senses.

In 1951, Wythe moved back to California and set up shop. His buildings are scattered around the country; many can be found on the Monterey Peninsula where he lived, and several are in the Idaho panhandle. He and his wife, Lois, moved to northern Idaho in 1977 and bought land on Lower Pack River, where they built, in pleasing curves, a home called Unicorn Farm. It’s at the end of a driveway that arcs through the woods, and two of its curves come to a point overlooking a woodland pond.

“The last project I’ve worked on is always my favorite,” said Wythe, but Unicorn Farm is perhaps the one of which he is most proud. “I wanted to do at least one project where everything came out right. On other projects, owners always want to change something.”

Wythe’s current efforts are focused on preparing an introductory text, “Organic Architecture,” for high school students who are thinking of going into design and construction. It is important for them to learn about this approach before they get to college, he said, because it’s still not taught in most schools of architecture.

Sir,

I read your Spokesman-Review, letter to the editor online yesterday (today is 11/30).

Though I appreciate your opinion, I can give no more than appreciation for your attempt at revisionist history….from the perspective of someone in the “communications center”.

Your suggestion that the a-bomb be tested in an uninhabited area was 70 years too late, and had been done prior to dropping it on Hiroshima. Your credit to Stalin for ending the war against Japan because the Japanese…..were so fearful of the Soviet military is, in my opinion, ridiculous. The Russians army, though successful in defeating the Nazi’s on the Eastern front and in devastating Berlin, to the tune of the rape and abuse of tens of thousands of German women, was suffering from a enormous number of casualties in their battles. I doubt they would have had the ability to turn about and march East to confront the Japanese.

Why, in God’s name, did you decide to voice your imaginary opinions on this subject 70 years after the fact?

You sound angry and anti-American. Maybe you should leave it alone until you can get more than bleeding heart perspective being in a room that afforded you the opportunity to be a part of history.

Your military acumen leaves a lot to be desired.

David Bray

Spokane