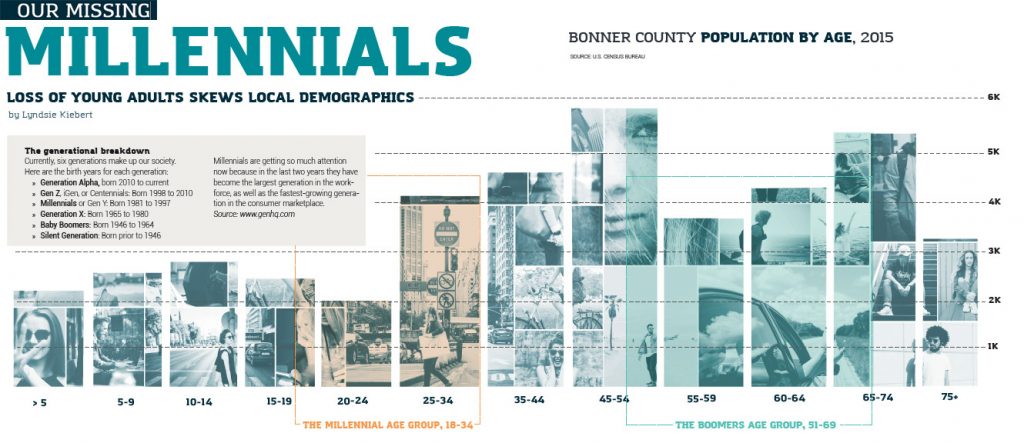

OUR MISSING MILLENNIALS

From the Winter 2018 Issue

graph/illustration by Pam Morrow

Over the last decade, Bonner County’s population grew as expected—on the surface. Sam Wolkenhauer, an economist with the Idaho Department of Labor, has studied Bonner County’s unique situation, looking beneath the county’s predicted growth to understand what is really happening.

“The total numbers hid that underneath you had millennials moving out and baby boomers moving in,” Wolkenhauer said. “There was almost an equitable swap that hid what was happening to the demographics.”

Wolkenhauer quantifies that equitable swap simply: in 2015, there were almost 6,000 missing millennials who had been replaced by baby boomers who had moved in.

“What makes Bonner County so unique is that you have this aging trend in counties in Idaho, but most are much smaller,” Wolkenhauer said. “Of counties that are of an equivalent age, Bonner County is the largest.” In other words, Bonner County, population about 42,000, is the largest county in the state to have so many older residents.

While consequences of such a dramatic shift could vary from political to social to economic, Wolkenhauer said the impact on the economy is most prevalent.

“The big economic consequence is labor. When more and more of your population is retired it creates a real squeeze for employers.”

In a 2015 report by Headwaters Economics, studies revealed that non-labor income—including investment income, pensions, Social Security, disability and welfare—has grown to be “more than half of total personal income in Bonner County (rising from 31 percent of total personal income in 1970, to 43.8 percent of total in 1990, to 53.7 percent of total in 2013).” This reflects a community that is retired, choosing not to work, and/or is unable to work for some reason.

Wolkenhauer said that in 2000 in Bonner County, about 56 percent of all adults were working. Now, only about 50 percent are, which is far below the national working rate. He said this is largely due to the increasing number of retirees in the county.

And according to Wolkenhauer, this demographic shift and its consequences on the labor market will only increase in the coming years, based on these trends.

“People know that the baby boomers are retiring, but what people don’t think about is that most of them haven’t yet because they are a backloaded generation,” he said. “It’s a big generation in general, but most of them are in their late 50s and early 60s.”

So where are our millennials? Where did they go, and why? And of those who stayed—how did they do it, and how do they manage to live in a county that becomes increasingly less conducive to working people in their 20s and 30s?

Millennials, born between 1981 and 1997, are either launching their careers right now or settling into their field, depending on their age. Tyson Bird, a 2014 graduate of Sandpoint High School, is on the younger spectrum of the millennial generation, and is currently finding his way away from Bonner County, despite his love of his hometown.

“People ask, ‘Why would you ever leave?’ and my response is always that it’s an awesome place to be from, but to actually make a living there is harder than you can imagine,” Bird said.

“The jobs that I wanted to do… it was hard to find those jobs in the community.”

Bird said he pursued his interest in media and graphic design while he still lived in Sandpoint pre-college, but found no media outlets exploring design in a large-scale, multi-platform, collaborative way.

“Media in no city is perfect, but there are some places that are helping people like me move into that space more,” he said, adding “that space” would mean a career that allowed him to use design in a way not practiced in Sandpoint.

After attending college in Indiana, Bird took a job working for Gatehouse Media in Austin, Texas. In his everyday work as a digital designer, he creates digital media packages to accompany news stories from newspapers across the country.

Bird said he is proud to be from Sandpoint, but added that same pride can be a hindrance for the region.

“People can be resistant to change, and that’s okay because we have kept this status as a gem (of the Northwest),” Bird said. “But to do the things I wanted to do, I had to leave.”

On the other side of the coin is Jennifer Koopman, a 2005 graduate of Clark Fork High School. On the older end of the millennial spectrum, Koopman left the area to play college volleyball, ultimately earning her degree in radiographic science from Lewis-Clark State College after moving around the Northwest and getting married.

“I really wanted to come back here because I really love it here and I think moving away makes you appreciate what’s here. So I researched this whole area and did whatever I could do to get a job,” she said. “I’d say I got really lucky.”

Koopman is currently a CT scan technologist for Bonner General Hospital—the second-largest employer in the county next to the school district—and her husband works for the Forest Service.

“We always kind of joke that you have to find a job that lets you live here,” she said.

Koopman said that the biggest draw for her is the geography of the area.

“In Portland, people would say ‘Let’s go to the lake’ and we’d drive hours,” she said. “I (grew up) in the most beautiful place, and the people were so nice, and so for me it was like, I want to go home to where if you want to do nature, you don’t have to drive hours.”

While she and her husband were fortunate enough to enter fields that allowed them to have careers in Bonner County, Koopman said her brother, Aaron Gauthier, who has a degree in mechanical engineering, has found it hard to give up the money he makes in the Texas oil industry and come home.

“You get used to a lifestyle of money and you start to think, ‘Yeah this is what I should be making,’ especially after you put in eight years of college,” Koopman said. “He tried hard to come back, but there wasn’t anything that paid even remotely what he expected.”

While Koopman loves the area, finding somewhere to live wasn’t easy, she said. When she and her husband decided to buy a home, they learned a lot about the area’s housing market quickly.

“It was eye-opening more than anything. We went in with a budget and an expectation, but after looking around you realize really quickly that that’s not what you’re going to get. You’re going to pay a lot for a little,” she said. “You’re paying to live here, not for your house. You’re paying to live in this area.”

That’s a sentiment felt across the board, according to Wolkenhauer. Millennials, especially on the younger end, aren’t looking to buy, but rent in Sandpoint isn’t cheap.

“Sandpoint is a resort town—that’s understandable and justifiable,” he said. “So building is always going to be lopsided, with houses rather than multi-family apartment complexes.”

With labor jobs so scarce and rent so high, how does a 20-something manage? Evan Metz, a 2011 graduate of SHS, takes on Bonner County’s unique situation by owning a business.

With labor jobs so scarce and rent so high, how does a 20-something manage? Evan Metz, a 2011 graduate of SHS, takes on Bonner County’s unique situation by owning a business.

Metz co-owns the downtown coffee stand Understory Coffee and Tea. Since graduating, he said he’s traveled to places similar in geography to Bonner County without finding a place quite the same.

“Most of those places are played out,” Metz said, mentioning McCall, Idaho, and Lake Tahoe. “Sandpoint is a relatively blank slate.”

Metz said his network of Sandpoint friends hold largely seasonal jobs, “migrating from gig to gig” as jobs begin and end.

“Everybody who has started something has gone somewhere else,” he said, adding he is trying to combat the idea that Sandpoint is just a town of “old retired people” by being here. “I’m excited to be where I’m at because I want people my age to see what I’m doing and think, ‘Hey, maybe we can carve it out there, too.’ I want to inspire other people to come and disrupt the system.”

Still, Metz recognizes that his home county’s demographic makeup is beneficial in a lot of ways, both socially and politically.

“I see it as a moderate place,” Metz said, mentioning that he’s travelled to more traditionally liberal places thinking he’d find more solace, only to crave more moderate viewpoints. “Part of the magic in the water here is how mixed it is politically.”

Metz said he intends to stay in the area until he feels he’s reached his goals as a business owner, and while he’s not sure what that will look like, he knows Sandpoint is where he wants to be.

“This area produces rad people, and that makes you proud,” he said.

What those rad people need, according to Metz, is a refreshed view of what Sandpoint can offer to young people—specifically millennials.

Bird believes communication is important. “First, people need to really talk about (the potential for) business and industry, and remember there is also a really great school district,” Bird said. “[Sandpoint] is more than a vacation destination.”

He believes investing in the entrepreneurial endeavors of young people is also critical to encouraging a millennial crowd to stay in the Sandpoint area.

“What’s very appealing to a younger crowd is this idea that they can invest and get something going,” he said. “You can still have traditions, but you should also be open to new ideas.”

What does Bonner County have in store assuming this trend of baby boomers replacing millennials continues? Sam Wolkenhauer said the consequences will certainly be felt on an economic level.

“I think the reason people should care (about the lack of millennials in Bonner County) is because if you don’t have a millennial workforce, you won’t have a workforce 15 to 20 years from now,” Wolkenhauer said. “You won’t have enough labor to provide the services people are used to, and I imagine that will cause people to move away.”

While consequences of such a trend on a social or political level are difficult to quantify, Metz said he sees value in living in a place full of both millennials and baby boomers, likening it to the “melting pot” concept.

“What makes a rich community is a culture of young blood and old blood,” he said.

The generational breakdown

Currently, six generations make up our society.

Here are the birth years for each generation:

- Generation Alpha, born 2010 to current

- Gen Z, iGen, or Centennials: Born 1998 to 2010

- Millennials or Gen Y: Born 1981 to 1997

- Generation X: Born 1965 to 1980

- Baby Boomers: Born 1946 to 1964

- Silent Generation: Born prior to 1946

Millennials are getting so much attention now because in the last two years they have become the largest generation in the workforce, as well as the fastest-growing generation in the consumer marketplace.

Source: www.genhq.com

Do Millennials matter?

What kind of impact can a loss of millennials have on a community?

In Broad terms…

- M’s are the generation having children, so fewer M’s in a community inevitably means fewer children. This leads to declining school enrollments. In an area where funding is tied to enrollment, this translates to less funding for education.

- M’s make up the majority of the workforce. Major businesses are not attracted to areas with an insufficient base of workers.

- M’s prefer public transportation over personal cars. Boomers seem to LOVE their cars. A community with fewer M’s, therefore, is likely to give less importance to public transportation.

- M’s rely on technology, so communities that attract M’s offer truly high-speed internet and lots of public wi-fi.

Leave a comment