Relearning Salish

From the Winter 2019 Issue

Pend Oreille’s ancient language lives again

In centuries past, English was not a language heard in the areas around Lake Pend Oreille. Other languages and dialects dominated; most notably Kalispel, a Salish dialect spoken by the Kalispel Tribe, whose territory stretched from what is now Washington, through the Idaho Panhandle and over into what is currently Montana.

The lake itself, and the river that flows out of it, gets its current name from what early French trappers and settlers called the tribe: the Pend d’Oreilles, after the large shell pendants hanging from their ears. They called themselves the Qlispé, the “Camas people,” after the purple-flowering wild plant whose bulbs provided them with an important food staple.

Concurrent with European settlement of the region, the language was split geographically along with the tribe, and the Kalispel people were relegated to reservations in Montana and Washington. The Kalispel language is closely related to Bitterroot Salish (also called Montana Salish), which is spoken by members of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana.

Kalispel is also closely related to Spokane, and slightly more distantly, Colville-Okanagan, Wenatchee-Columbian and Coeur d’Alene. All are, to some degree, mutually intelligible (that is, they can generally understand each other), which has led some linguists to describe them as dialects of Interior Salish rather than separate languages, although what constitutes a language rather than a dialect is up for debate.

Tribal histories say that all these languages, along with the coastal Salish languages and more northern Salish languages, came from one great tribe. The story goes that the tribe spread out, over hundreds of miles, and became many tribes. Linguistically, this makes sense: it’s approximately what happened when Latin spread out and became Spanish, Italian, French, and the various, less-spoken Romance languages of Europe.

Currently, each Interior Salish language or dialect has only a handful of elders who still speak it, if they have any. In the last century, in schools and in society at large, tribal members were discouraged from speaking their native language. As a result, the language nearly went extinct. However, revitalization programs have brought it to life again, something that has been a group effort.

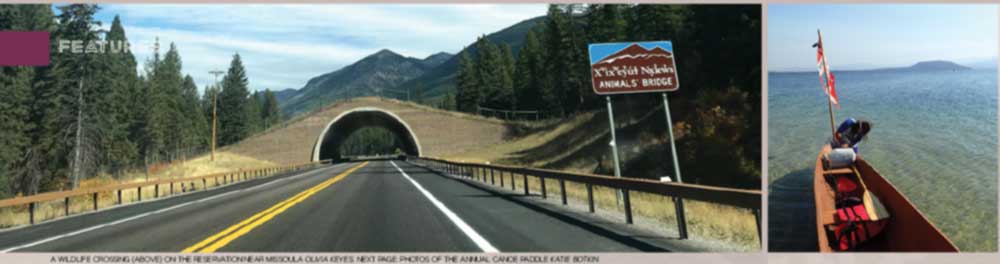

Historically, the Interior Salish Tribes visited one another, celebrated together, and intermarried. Now, in their language revitalization and in reclaiming their cultural practices such as traditional canoe-making, they are working together again. For the past few summers, for example, they have paddled rivers together in dugout canoes. The past two years, the Kalispel have undertaken an annual paddle on their traditional waterways, exploring Hope, docking at Sandpoint City Beach, and paddling downriver to their powwow grounds near Usk, Washington. They were joined by area tribes such as the Colville and Spokane. Some incorporated Salish into their paddling; the young skipper of the Spokane canoe counted off strokes in Salish to his crew, and sang in Salish as the canoe passed Dover.

The tribes also borrow language curriculum and best practices from one another, and they attend the annual Salish conference together. Held in the Kalispel Tribe’s casino and resort in Airway Heights, Washington, the Salish conference conducts immersion sessions, holds Salish karaoke, and brings hundreds of Salish speakers from the Inland Northwest together.

Language revitalization for the Kalispel Tribe follows parameters set out by Spokane, its Salish sister. JR Bluff, language director for the Kalispel Tribe, said the Kalispel language program started about 10 years ago, and “at least for the past six years, we’ve been knee-deep” in teaching Kalispel. Bluff credits Chris Parkin, “the guy behind Salish School of Spokane,” with developing “our path, our curricular methodology.” Currently the principal and acting business manager of the school, and a former Spanish teacher, Parkin shared his curriculum with the Kalispel Tribe. Afterwards, said Bluff, “we converted it to Kalispel Salish.”

The Kalispel Tribe now has multiple language programs going. They hold a K-4 immersion school, where elementary students will learn about 500 Kalispel words in three weeks, said Bluff. For the immersion school, “all of our parents have a pretty big buy-in to what we’re doing.” They have high school and community programs as well, and they also hold a year-long language intensive where students study Kalispel for eight hours a day. Generally, five to eight students enroll in this language intensive, said Bluff. “It’s more of an adult class, and all of them work for the tribe” in some capacity, he specified. Typically, people go through the intensive prior to teaching Kalispel.

Bluff and language program coordinator Jesse Isadore organize the Salish conference. Bluff said that he wants all the Interior Salish tribes to be represented in the program. “I want it to come from different tribes, I want somebody from each one of their tribes to present,” he said. As for what kind of content he’s looking for, he says he wants proposals from people who are on the ground, doing the work. So rather than some PhD student with theories, he picks the “Joan Walker teaching kindergarten.”

The Salish conference gathers people who might feel isolated into a group of like-minded individuals, Bluff says. At the conference, elders speak in Salish and young children talk to their parents; generations mix and converse together in the ancestral dialects of the region.

At last year’s Salish conference, tribal youth from UNITY council spoke to the younger generation, introducing themselves in Salish and openly discussing their struggles. They identified the language as one way to reclaim their cultural identity, and spoke of a calling to live committed, drug-free, alcohol-free, service-minded lifestyles that benefitted their communities. “Helping my people is what makes me feel good,” one teenage girl told the gathering of younger kids. “Love is the most powerful thing in the world. So I encourage you to get out and help your community.”

Visit the Kalispel Tribe’s language pages at www.sptmag.com/salish

Leave a comment