These are the MOOSE of our lives

From the Winter 2019 Issue

staci bailey, annie pflueger, John Proctor, dabne sparks

Big, bold, and not-very-endangered, moose are a staple of North Idaho life

In the deep, shadowy woods of Idaho—along with Scandinavia, Canada, Siberia, and almost everywhere else with wild country north of the 40th parallel—lives a dark beast of considerable size, and in considerably greater numbers in our part of the world than there were 110 years ago. It is bristly, solitary much of the time, ill-tempered, somewhat fearless and, according to some, quite tasty.

It is not a bear. Or a wolf. Or a Sasquatch.

Behold the moose, the largest ungulate; Latin name, Alces alces, which means “moose moose.” Or, “elk elk,” which is what the rest of the world calls what North Americans call moose.

Ungulates are creatures with hooves, including the deer family, of which moose are members. Like most of the deer family, moose are herbivores. They have sharp, incisive front teeth in the lower jaw and a hard palate in the upper jaw, used in combination to chop off herbage; and huge molars at the back of both jaws with which to masticate the often tough and fibrous stuff they manducate. They browse on all sorts of trees, shrubs, forbs, and grasses, including tasty underwater plants found in lakes large and small. They hold their heads underwater for up to a minute as they graze in the shallows.

Moose have large feet built to wade through silty muck and deep snow, and legs adapted to swimming, brush busting, and navigating big snow drifts. Long and immensely strong, those legs have highly flexible front knees and shoulders, allowing them to easily pick their front feet out of deep snow or lake-bottom mud. Their tracks are distinguished by their size, with elongated, pointed toes, which often leave wavy impressions because of their flexibility.

Moose live between 15 and 25 years. They breed in early October, and have an eight-month gestation period, so calves are born late May or June. Twins are not uncommon. The youngsters stay with their mother for about 18 months, at which point they are “abandoned” to fend for themselves. The female will tolerate a female calf for longer, but bull calves get chased off.

Though moose are associated with swampy places, they can be found in almost any forest habitat at any time of year. It’s not uncommon to find winter moose tracks in the subalpine forests of Schweitzer in the Selkirks. They are seen browsing on bushes high in the Scotchman Peaks and eating water plants along the shores of Sand Creek. They are also, and often, seen browsing through yards, parks, and landscapes all over Sandpoint.

“Moose,” by the way, is singular or plural. “Moose’s” means it belongs to one or more moose. North Idaho is a moose’s paradise.

Big, bold, and not very endangered

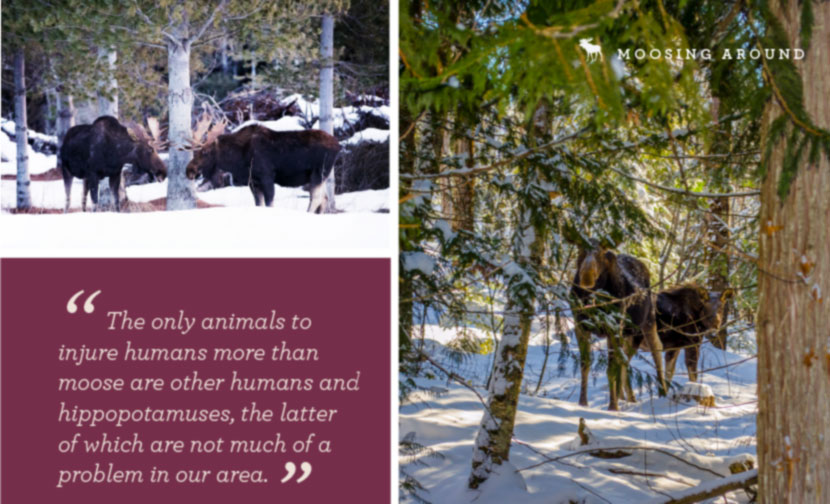

Moose have a permanently installed “do not disturb” sign on their foreheads. You may not be able to see it, but it’s there, and it’s a good idea to honor it. The only animals to injure humans more than moose are other humans and hippopotamuses, the latter of which are not much of a problem in our area. When upset, in spite of its size, a moose can move very quickly, and those beady little eyes see very well what they might wish to harm. Dog owners, beware. Don’t let your dog chase a moose unless you want to get a new dog.

They are big, bold and not very endangered. In fact, there are more moose in North Idaho now than there were in the 1970s. Many more. Which could explain why some have moved out of the woods and into town. And not just Sandpoint, where they sometimes become resident. Larger bergs, such as Coeur d’Alene, Spokane and Wenatchee, have regular moose visitations. During the winter of 2001-’02, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game moved about 100 moose out of the Idaho Falls area.

Moose come to town because they like ornamental shrubs, fruit trees, tulips, and Norway maples as much as they do aspen, ninebark, water weeds, and other wild browse.

The best way to confront a moose is not to. Idaho Fish and Game personnel, various city police departments and the web page for the city of Sandpoint (www.sptmag.com/reportmoose) all advise to leave a visiting moose to its own devices.

That’s good advice. Bulls in rut and females with calves are exceptionally dangerous. They don’t go looking for trouble, but when they encounter what they perceive as a threat, they turn aggressively nasty. Acting like a papparazzo when you’ve spotted a moose can qualify as threatening.

While grizzly bears tend to get most of the ink, with best-sellers like “Night of the Grizzlies” or “The Bear’s Embrace,” moose should always be taken seriously. Do not, repeat, DO NOT approach a moose on the street to give it a pet, and if a moose happens to have a baby in tow, be especially careful to keep your distance.

Moose are large. In the animal kingdom, they wear XL hides. The only terrestrial mammals larger are hippos, rhinos, elephants, and the occasional Alaskan brown bear. Males can be seven feet tall at the shoulder and weigh up to 1,500 pounds, plus antlers. Females can weigh in at 1,000 pounds, but they are not much shorter than males. Both genders can and regularly do step over four-foot fences without scratching their bellies. The tulips are always greener on the other side of the fence.

The price of mooseburger and how to get it

For those who relish mooseburger, it is not easily come by nor inexpensive. In Montana, Idaho, and Washington, moose tags are issued by lottery. As an example, in 2015, 6,498 Idaho hunters entered a drawing for 873 Idaho moose tags, which included both genders. Of those, 680 tags were filled (meaning a moose was harvested).

That might not seem like a big number, but in 1900, it would have been, compared to the Idaho moose population at that time, of which there was almost none. In fact, the state closed moose hunting in 1898 to prevent extirpation. By 1910 a small recovery had been made, and there were an estimated 500 in the state. By 1939, there were about 1,000 and in 1946, IDFG issued 30 moose permits. Since then, the population has expanded exponentially, with a peak of over 12,000 moose in the state in 2002. In 2018, there are still over 10,000.

While the moose population has increased, moose fervor seems to have abated. In 1980, over 25,000 hunters entered the lottery for just 170 permits—almost four times the 2015 number.

Idaho residents can still get mooseburger for a reasonable price if they don’t count the cost of equipment or their time. In addition to a $30.50 hunting and fishing license, an Idaho resident tag for a moose is $216.50, plus a $16.75 lottery application fee (compare elk tags at $16.50).

Non-residents might as well just go buy an entire Kobe beef—their tag costs $2,143.50 plus a $41.75 application fee, after they pay $154.75 for a hunting license. This doesn’t include airfare, guide services, or cigars and single malt scotch for hunting camp. Idaho permits are limited to once-in-a-lifetime for either gender, which means that if a hunter is extra lucky, she may be able to draw permits to take a male and a female moose during her time on Earth.

Montana moose are cheaper if not easier to get. A Montana resident license for moose is $125, plus a $10 application fee. Non-resident is $1,250, plus $50.

Management by man and beast

IDFG moose management philosophy is to allow the harvest of bulls at levels that will allow populations to continue to expand. Bulls are defined as having at least one antler longer than six inches.

Harvest of cows (a female moose, if you didn’t know) is designed primarily to reduce moose population growth, promote human health and safety where moose occur in suburban settings, and limit moose depredations. Moose hunting seasons are long: 86 days for bulls from the end of August to November. Hunting season for cows is about 40 days between mid-October and the end of November. One reason cow seasons don’t begin until mid-October is to reduce potential orphaned calves.

Besides humans, moose have only one predator of any consequence, and that is the wolf. Bears and mountain lions also prey on moose, particularly the calves, but worldwide, it is the wolf that is most effective. In Alaska, Canada, and Siberia, which have much higher moose concentrations than our moose “paradise,” the predator-prey dance between moose and wolves is constant. The two species seem to be somewhat symbiotic, with the moose providing sustenance for the wolf and the wolf providing disease and population control for the moose.

In North Idaho, there are not so many wolves, which may be one of the reasons why Alces alces has thrived here. In any case, they are a successful conservation story in the Northwest, and in Idaho particularly.

The writer of this article is great! Informative and clever. Enjoyed it a lot.